Uganda is one of the most wildlife species-rich countries on the African continent, home to over 345 mammal species, more than 1,065 bird species, and a network of protected areas that support everything from rainforest primates to savannah carnivores.

For visitors focused on wildlife, it presents a rare opportunity: the ability to see mountain gorillas, chimpanzees, lions, elephants, and shoebills without crossing a border.

The country’s safari offer centres around ten national parks and over a dozen game reserves. Queen Elizabeth, Murchison Falls, and Kidepo Valley are key strongholds for big game. Bwindi and Kibale protect Uganda’s primate populations.

Each protected area has distinct ecological zones, from lowland swamps and papyrus channels to montane forest and open acacia grassland. That variation gives Uganda an edge: you see different animal communities in relatively proximity.

Moreover, Uganda’s tourism sector is tightly linked to conservation. Revenue from gorilla trekking permits directly funds wildlife protection and community infrastructure. Anti-poaching teams operate in all major parks.

Data collection using GPS collars and camera traps supports ongoing wildlife research, especially on elephants, lions, and great apes. When you visit, you’re stepping into one of the most intricate and evolving conservation systems in East Africa.

If you’re planning a safari in Uganda, this guide lays out what animals you can expect to see, where to see them, and what makes each species significant in the context of Uganda’s wildlife economy.

The Headliners: Uganda’s Big Five

The Big Five: lion, elephant, buffalo, leopard, and rhinoceros, serve as a benchmark for many safari-goers. In Uganda, each one represents a distinct ecological zone and conservation story. While some are reliably spotted in national parks, others require a specific plan and local knowledge to find.

African Lion (Panthera leo)

Uganda’s lions are most frequently seen in Queen Elizabeth National Park, especially in the Ishasha sector, where a unique behavioural trait sets them apart. This is one of the few places in the world where lions regularly rest in fig and acacia trees. Researchers believe this climbing habit may help them escape heat and insect bites. Population estimates vary, but a 2021 UWA report placed Uganda’s total lion numbers between 350 and 400 individuals. Queen Elizabeth, Murchison Falls, and Kidepo Valley are the key habitats.

African Elephant (Loxodonta africana)

Both savannah and forest elephants are present in Uganda, though distinguishing between the two can be challenging in the field. Murchison Falls National Park has the highest concentration, with over 1,300 individuals recorded. These elephants often move in family groups and can be seen along the Victoria Nile or near the Buligi game tracks. Forest elephants, slightly smaller and darker, inhabit Kibale and Bwindi but tend to be elusive.

African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer)

Uganda hosts large numbers of Cape buffalo, particularly in Queen Elizabeth and Murchison Falls parks. They are highly gregarious, forming herds of up to several hundred. These animals are a cornerstone of the savannah ecosystem. You’ll often see them wallowing in mud or standing alert in tall grass, often with cattle egrets perched on their backs.

Leopard (Panthera pardus)

Solitary and nocturnal by nature, leopards are present in most major national parks but are harder to spot. Queen Elizabeth and Lake Mburo offer the highest sighting rates, especially during early morning or night drives. Their camouflage and patience make them formidable ambush predators. Rangers in Murchison Falls often rely on recent kill sites or monkey alarm calls to locate individuals.

White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni)

Rhinoceroses were once widespread across Uganda but became extinct in the wild by the early 1980s due to poaching and conflict. Today, the only place to see them is the Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary, a 70-square-kilometre private reserve located off the Kampala-Gulu highway. As of 2024, the sanctuary hosts 33 southern white rhinos, all part of a long-term reintroduction strategy led by the Rhino Fund Uganda. Visitors can track rhinos on foot with guides, offering a close-range experience uncommon elsewhere.

For safari planners, understanding the distribution of these five species is essential. No single park hosts all five, which means you’ll need to build your itinerary strategically. Uganda doesn’t hand you the Big Five on a platter, but it rewards those who look carefully.

The Icons: Species Unique to Uganda or Rare Elsewhere

Certain species put Uganda in a category all its own. These are animals you won’t just see anywhere. Some live only in specific ecological pockets. Others are globally rare and highly protected.

Uganda offers front-row access to a few of the planet’s most exclusive wildlife experiences.

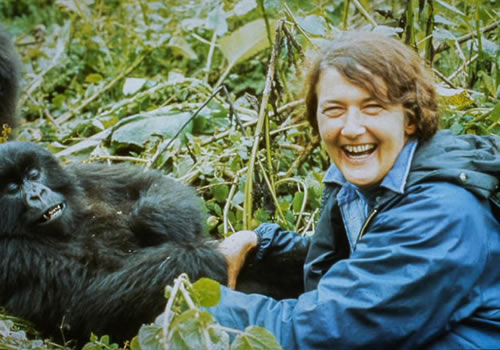

Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei)

Fewer than 1,100 mountain gorillas exist worldwide. Over half of them inhabit Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, with a smaller population in nearby Mgahinga Gorilla National Park. Gorilla trekking here is strictly regulated. Only eight visitors are allowed per habituated group, with one hour allotted for observation. Permits currently cost USD 800 per person, a fee that funds both conservation and community development. Gorilla groups in Bwindi are tracked from four sectors: Buhoma, Ruhija, Rushaga, and Nkuringo. Each has its own topography and logistical quirks. If you’re planning this, build in an extra buffer day. Weather delays and tracking duration can be unpredictable.

Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii)

Uganda has one of Africa’s most accessible and researched chimpanzee populations. Kibale National Park alone supports about 1,500 individuals. The Kanyanchu visitor centre is the main entry point for tracking. Habituation experiences (which allow up to four hours with the chimps) are also available. Chimpanzees are semi-terrestrial and move fast, often vocalising, feeding, or grooming in forest clearings. Besides Kibale, chimpanzee tracking is offered in Budongo Forest (part of Murchison Falls Conservation Area), Kalinzu Forest near Queen Elizabeth NP, and the less-visited Toro-Semliki Wildlife Reserve.

Shoebill Stork (Balaeniceps rex)

This prehistoric-looking bird is high on the list for birders and photographers. Standing over four feet tall with a massive, shoe-shaped bill, the shoebill looks like it belongs in a museum exhibit. It thrives in papyrus swamps and slow-moving wetlands. The best-known site for sightings is Mabamba Swamp on Lake Victoria, reachable from Entebbe by boat or vehicle. Shoebills are also occasionally seen in Murchison Falls National Park, especially near the Nile delta. The global population is estimated at under 5,000 individuals, making every sighting a privilege.

Golden Monkey (Cercopithecus kandti)

Restricted to the high-altitude forests of the Virunga Volcanoes, golden monkeys are striking in both colour and behaviour. Mgahinga Gorilla National Park offers the only guided tracking experience for this species in Uganda. Troops move quickly through bamboo zones and mid-elevation forests, feeding on fruits, leaves, and invertebrates. Photography can be challenging, but sightings are usually reliable. Compared to gorilla or chimpanzee treks, golden monkey treks are less physically demanding.

Tree-Climbing Lions (a regional behaviour, not a subspecies)

Mentioned earlier under the Big Five, these lions in the Ishasha sector of Queen Elizabeth NP deserve repeat attention. This behaviour is not consistent across all lion populations. In Uganda, it’s hyper-localised. Lions here are frequently found sprawled across fig branches in the midday heat. Timing matters. Arrive between 11 a.m. and 2 p.m., and work with a guide who knows the individual prides by name and range.

Each of these species plays a role in defining Uganda’s wildlife offering. Their presence signals ecological integrity, targeted conservation, and biological uniqueness. If you’re organising a safari around specialised species access, start with these.

Classic Safari Wildlife

Beyond the icons and primates, Uganda supports a broad spectrum of classic safari species.

These are the animals that define the savannah experience: hoofed herbivores, stealthy predators, river giants, and scavengers.

They’re widespread, often seen in mixed assemblages, and vital to the health of Uganda’s protected ecosystems.

Plains Zebra (Equus quagga)

Zebras are common in Lake Mburo National Park and Kidepo Valley. Lake Mburo, located roughly 240 kilometres west of Kampala, is Uganda’s best site for reliable zebra sightings. Unlike Grevy’s or Hartmann’s zebra, Uganda’s population belongs to the plains subspecies, which forms large herds and grazes alongside impala, eland, and topi. Their black-and-white striping serves as visual confusion for predators and may aid in temperature regulation.

Rothschild’s Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis rothschildi)

This subspecies is classified as vulnerable and was once limited to Murchison Falls National Park. Recent translocations by the Uganda Wildlife Authority have re-established populations in Lake Mburo and Pian Upe Game Reserve. Rothschild’s giraffes have pale markings, five ossicones, and no markings below the knees. Murchison remains the stronghold, with over 1,600 individuals, especially visible near the southern game tracks.

Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius)

Hippos are widespread in Uganda’s lakes and rivers, especially within Queen Elizabeth and Murchison Falls national parks. During the day, they remain submerged in water bodies to regulate body temperature. Nighttime is feeding time, and they often roam surprisingly far from the waterline. Kazinga Channel, which links Lake George and Lake Edward, is a hotspot. Boat cruises offer near-guaranteed sightings.

Nile Crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus)

Crocodiles share many of the same aquatic zones as hippos. The Nile stretch below Murchison Falls is known for particularly large specimens, some exceeding five meters in length. These reptiles are ambush predators, feeding on fish, birds, and the occasional ungulate. Dry-season months reveal them sunning along sandbanks and river bends.

Ugandan Kob (Kobus kob thomasi)

This antelope is both a national symbol and a dominant grazer in Queen Elizabeth, Murchison Falls, and Kidepo Valley. Males display striking reddish-gold coats and often gather in leks—open display grounds where they compete for females. Their presence signals good grass cover and predator density, since they’re a preferred prey for lions.

Other Common Mammals

Warthogs, olive baboons, vervet monkeys, bushbucks, waterbucks, and oribi round out the list of regularly seen mammals. Lake Mburo is the only park where impalas are found. Kidepo hosts Jackson’s hartebeest and large eland herds. Baboons often linger near park gates, sometimes too close. Keep your windows shut.

Classic safari species in Uganda don’t always steal the spotlight, but they form the ecological stage on which the rarer wildlife depends. Tracking lions or gorillas might top your list, but the consistency of these animals is what makes a multi-day game drive worth it.

Birding Paradise

Uganda has recorded over 1,060 bird species, representing around 10 per cent of the world’s bird population and more than half of Africa’s.

The GREY CROWNED CRANE, Uganda’s national bird, is both visible and vocal. It favours wetlands and open grasslands, and pairs perform dramatic courtship dances during the rainy season. You’ll often find them near Lake Mburo or the Katonga wetlands, heads bobbing, golden crowns catching the light.

Mabamba Swamp, a short journey from Entebbe, is the most consistent site for SHOEBILL sightings. These storks stand over a meter tall and move with a stillness that unsettles the unprepared. Birding guides pole visitors through papyrus in traditional canoes, scanning the edges for this elusive species. Beyond Mabamba, sightings are possible in Semliki, Murchison Falls, and the Nile delta zone, but require early starts and expert navigation.

Uganda’s southwestern highlands are part of the Albertine Rift, a biodiversity hotspot that hosts over 20 endemic species. Bwindi Impenetrable National Park is the most productive site for them. Patient observers, preferably with local guides, can target species like the RUWENZORI TURACO, HANDSOME FRANCOLIN, and PURPLE-BREASTED SUNBIRD.

These birds favour dense forest understorey and often reveal themselves through sound long before they’re seen. Kibale and Budongo Forests add additional forest-dependent birds like GREEN-BREASTED PITTA, CHOCOLATE-BACKED KINGFISHER, and BLACK BEE-EATER. Their ranges don’t overlap much, so a successful birding plan needs geographic spread.

Savanna parks also hold strong value. Queen Elizabeth and Murchison Falls support AFRICAN FISH EAGLES, SADDLE-BILLED STORKS, MARTIAL EAGLES, VULTURES, and numerous BEE-EATERS. Early morning game drives frequently double as productive birding excursions.

By contrast, Lake Victoria and the Kazinga Channel support excellent wetland birding. Sites like Lutembe Bay and Lake Opeta see seasonal fluctuations, especially between October and April when Eurasian migrants arrive in large numbers. Expect BARN SWALLOWS, SANDPIPERS, WAGTAILS, and the occasional raptor on passage.

Where to See Them

- Queen Elizabeth National Park

Known for its species density and variety, this park delivers on both mammal and bird sightings. Expect lions (including tree-climbers), leopards, elephants, hippos, Ugandan kob, and over 600 bird species. Boat cruises along the Kazinga Channel are a highlight.

- Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

The core site for mountain gorilla tracking. Also important for Albertine Rift endemics. Birding here is exceptional, if slow-paced, with species like RUWENZORI TURACO and GREEN-BREASTED PITTA drawing specialists.

- Murchison Falls National Park

Home to over 76 mammal species, including lions, elephants, Rothschild’s giraffes, and large crocodiles. Birdlife includes the SHOEBILL and AFRICAN FISH EAGLE. Boat trips to the base of the falls offer multi-species viewing.

- Kidepo Valley National Park

Remote but rewarding. Classic savanna species dominate: cheetahs, buffalo herds, zebras, ostriches, and eland. Visibility is high, especially in the dry season. Infrastructure is improving but remains light.

- Kibale National Park

Primary site for chimpanzee tracking, with over 1,500 individuals studied across decades. Also a forest birding hotspot. Guides track both habituated and semi-habituated groups depending on permit type.

- Lake Mburo National Park

Closest savanna park to Kampala. Good for zebras, impala, warthogs, and Rothschild’s giraffes. Lacks large predators, which allows for walking safaris. Birding includes ACACIA SPECIALISTS and seasonal migrants.

- Mgahinga Gorilla National Park

Best known for golden monkey tracking. Also hosts a small population of mountain gorillas. Birders come for high-altitude species and Virunga-specific endemics. Trails are steep but well-maintained.

- Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary

The only place in Uganda where you can track wild white rhinos on foot. Located along the Kampala–Gulu highway. Part of a long-term reintroduction program coordinated by Rhino Fund Uganda.

Why Uganda Commands Attention

Uganda doesn’t compete for attention but rather commands it. Its wildlife offering is deep, specialised, and often surprising. Mountain gorillas in misty valleys. Lions that rest in trees. Shoebills standing motionless in papyrus. These are ecosystem markers tied to long-running conservation frameworks and serious biological value.

The country’s national parks are not overrun. Its tourism model is grounded in controlled numbers, expert guiding, and local involvement. For planners, researchers, and investors, that presents a durable proposition. Species distribution is wide but knowable. Logistics takes effort but yields results. Uganda rewards planning with access to species that remain out of reach elsewhere.

If your interest lies in serious wildlife travel, whether as a visitor, a conservation stakeholder, or a tour developer, Uganda should be in the conversation from the outset.

Not for scale, but for integrity. Not just because of what can be seen, but because of how it’s protected.