Many people who embark on gorilla treks in Uganda, Rwanda, or the high-altitude forests of Congo grow familiar with a single image of the gorilla: thick black fur, a broad, muscular build, and the haunting presence of a silverback seated in mist. What often goes unspoken, even among seasoned trekkers, is that this iconic figure represents just one branch of a broader family or types of gorillas. The gorillas found in the Virunga Mountains and Bwindi Impenetrable Forest are mountain gorillas, a distinct subspecies with unique ecological traits, behavioural patterns, and conservation challenges.

But the story does not end there.

In the dense lowland forests of Kahuzi-Biega National Park, in a different ecological cradle of the Democratic Republic of Congo, another subspecies exists: lowland gorillas, often less known but no less significant.

These gorillas live and thrive in separate and distinct worlds altogether. To understand the difference between them is to grasp the remarkable adaptability of a species shaped by terrain, geography, and history.

Below, in this article, we explore the distinctions between mountain and lowland gorillas. This ranges from taxonomy and habitat to morphology, behaviour, and conservation status. Are you planning your first trek or deepening your knowledge as a conservation-minded traveller? This guide offers a grounded understanding of Africa’s two most iconic great apes.

READ ALSO: Gorilla Trekking in Congo

Taxonomy and Subspecies Overview

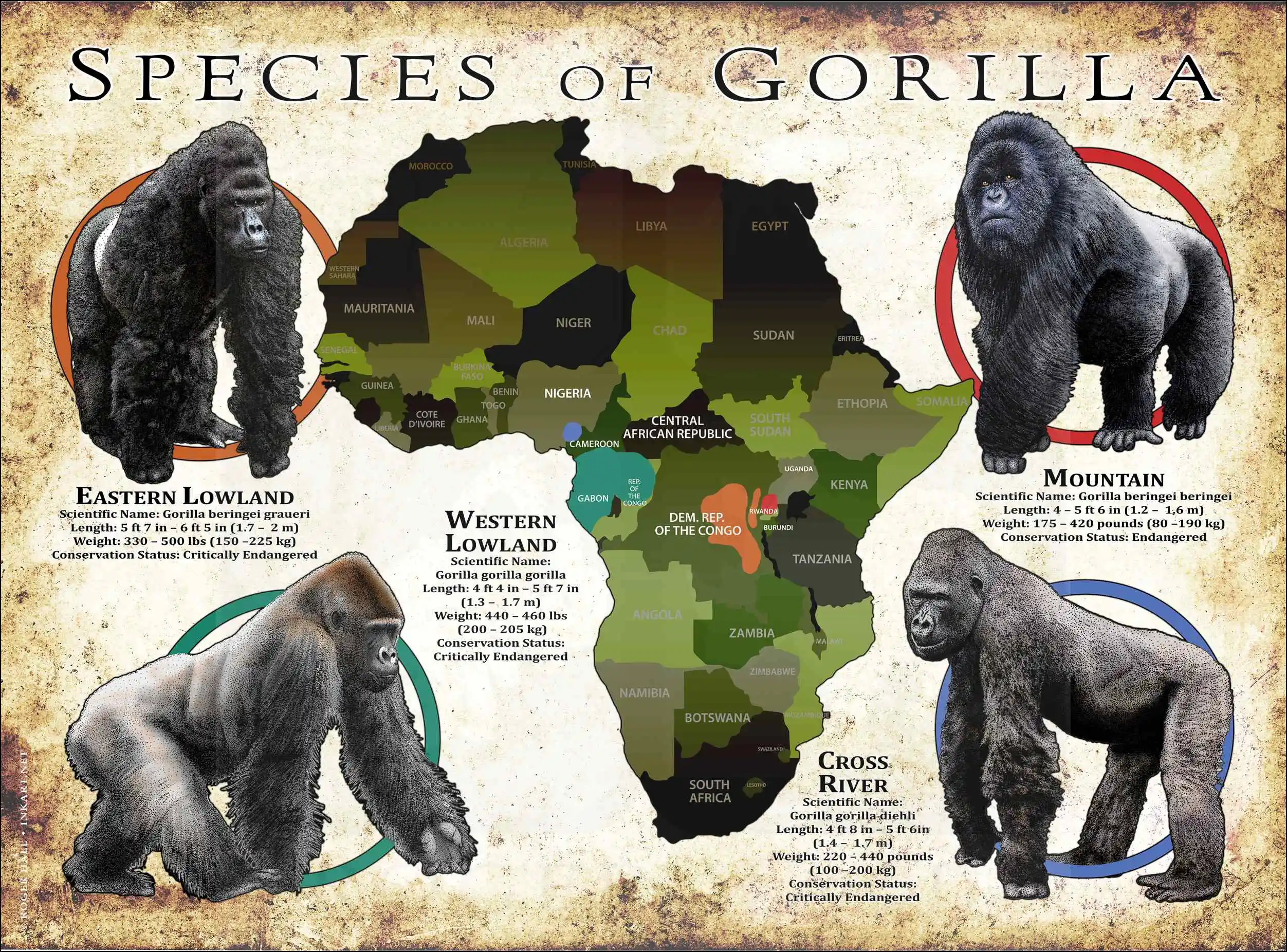

Gorillas belong to the genus Gorilla, classified under the family Hominidae, which includes chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. Within this genus, scientists recognise two main species: the Western Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) and the Eastern Gorilla (Gorilla beringei). Each of these species contains two subspecies.

Here’s how the classification breaks down:

Western Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla)

- Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)

- Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli)

Eastern Gorilla (Gorilla beringei)

- Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei)

- Eastern Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri)

The mountain gorillas often observed in Uganda, Rwanda, and the DRC belong to the subspecies Gorilla beringei beringei. They occupy high-altitude forests in two locations: the Virunga Massif and Bwindi Impenetrable Forest.

On the other hand, the lowland gorillas span two major groups. The Eastern Lowland Gorilla, sometimes called Grauer’s gorilla, inhabits the forested interior of eastern DRC. The Western Lowland Gorilla, far more numerous, ranges across the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, and parts of Equatorial Guinea.

Each subspecies has evolved in isolation, shaped by geography, food availability, and ecological pressures. Although they share a genus, their differences in morphology, behaviour, and conservation status are significant.

If you’ve been on a trek in East Africa, you have only seen one kind, but there’s more to this story than meets the eye.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Mountain Gorillas inhabit two discrete highland forest zones in East-Central Africa. The first is the Virunga Massif, a chain of extinct volcanic mountains that straddle southwestern Uganda, northwestern Rwanda, and the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo.

This range includes three national parks: Mgahinga Gorilla National Park (Uganda), Volcanoes National Park (Rwanda), and Virunga National Park (DRC). Elevations in this zone reach over 4,000 metres, with gorillas generally ranging between 2,200 and 3,800 metres.

The second area, the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest, lies further north in Uganda’s Kigezi Highlands. Though ecologically distinct from the Virunga chain, it supports a separate mountain gorilla population. The forest covers 331 square kilometres and includes steep ridges and deep valleys. Here, gorillas occupy slightly lower altitudes, between 1,160 and 2,600 metres, but still depend on cool, mist-fed forest canopies.

Lowland Gorillas, meanwhile, span a broader geographic belt across Central and West Africa, adapting to humid tropical forests, swampy basins, and flat or undulating lowlands.

- The Eastern Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) is confined to the eastern DRC, especially in Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Maiko National Park, and surrounding community forests. These regions sit between 600 and 2,900 metres, but most groups reside below 1,500 metres.

- The Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) occupies one of the largest continuous forest ranges among primates. Populations exist in the Republic of Congo, Gabon, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, and parts of northern Angola. Key sites include Odzala-Kokoua National Park in Congo and Lopé National Park in Gabon. Most live at altitudes under 1,000 metres, in equatorial forest zones with high rainfall and layered canopies.

Besides geography, the physical structure of each forest influences social dynamics, movement, and diet. Dense highland undergrowth, for instance, limits long-distance travel among mountain gorillas. In contrast, lowland forests allow wider ranges and greater dietary variety.

If you’re trying to visualise the difference, it helps to map their altitudinal comfort zones: mountain gorillas stay high, lowland gorillas stay low. A simple rule of thumb.

Physical Appearance and Morphological Differences

Mountain gorillas tend to have shorter limbs, a broader chest, and denser muscles compared to their lowland relatives. Adult males can weigh between 140 and 200 kilograms, with heights ranging from 1.4 to 1.7 metres when standing upright. Their forearms appear especially thick due to strong brachial muscles developed for climbing and stabilisation on steep ground.

One distinguishing feature lies in the coat. Mountain gorillas grow longer, shaggier hair, which helps regulate temperature in high-altitude forests. This hair appears darkest on the shoulders, arms, and back, especially in silverbacks whose saddles seem more sharply defined. The nostrils are also wider, with a shorter snout and more pronounced brow ridge.

Eastern lowland gorillas are typically taller, though slightly leaner. Adult males may reach 1.8 metres, with weights falling between 130 and 210 kilograms, depending on age and feeding quality. Their limbs are longer and more proportioned for terrestrial travel. Hair length is shorter overall, with a greyish or brownish tint sometimes visible on the back or thighs.

Western lowland gorillas show even lighter builds. The average male weighs around 140 kilograms, with a less bulky torso and a narrower chest. Their faces appear more angular, with a slightly protruding mouth and higher nasal ridge. Skin tone also differs slightly; some individuals have lighter pigmentation around the eyes or nose.

To the untrained eye, the difference may seem minimal. But once you’ve seen both species up close, the contrast is unmistakable.

Behavioural and Social Structures

Both mountain and lowland gorillas live in cohesive social units, typically led by a dominant silverback. These groups include adult females, infants, juveniles, and sometimes subordinate males. However, the group size and cohesion vary depending on subspecies and environment.

Mountain gorilla groups tend to be smaller and more tightly bonded. Most units include 10 to 15 individuals, although some reach up to 30. The silverback directs travel, mediates conflicts, and decides when to rest or feed. These groups remain stable over time, with members rarely dispersing once formed. Grooming and resting take place in close proximity, reinforcing internal cohesion.

Eastern lowland gorilla groups may include 15 to 25 members, though field data from Kahuzi-Biega National Park sometimes report larger units. Their social bonds are strong but more flexible. Adult females may transfer between groups, and subadult males occasionally form temporary alliances.

Western lowland gorillas exhibit less predictable group structure. They form smaller units, often 5 to 8 individuals, with weaker long-term cohesion. The dominant male still provides leadership, but group composition shifts more frequently. In some regions, solitary silverbacks have been observed shadowing groups, waiting to take over leadership when the opportunity arises.

Feeding behaviour differs notably across regions. Mountain gorillas rely heavily on herbaceous vegetation, such as thistles, nettles, and celery-like plants. They feed for extended periods and travel shorter distances: typically 500 to 1,000 metres per day. Their highland diet includes fewer fruits due to limited availability.

Lowland gorillas, in contrast, cover wider daily ranges. Western lowland gorillas may move up to 2 kilometres per day, following seasonal fruiting patterns. Their diet includes over 100 plant species, with a marked preference for figs, termites, and soft fruits. This mobility affects group spread and cohesion.

Communication includes vocalisations, chest-beating, facial gestures, and postural cues. Mountain gorillas use low grunts and huffs to coordinate movement or signal an alarm. Chest-beating in silverbacks remains a key display, audible over 500 metres in some cases.

Conservation Status and Threats

The Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) is classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. As of the most recent population surveys, approximately 1,063 individuals exist in the wild. These are split between two populations: around 459 in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, and over 600 in the Virunga Massif, which spans Rwanda, Uganda, and the DRC.

Mountain gorillas have benefited from intensive conservation management. Daily ranger patrols, veterinary interventions under the Gorilla Doctors program, and controlled ecotourism have helped stabilise their numbers. Uganda Wildlife Authority, Rwanda Development Board, and the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation all coordinate on shared protocols through the Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration.

Despite progress, threats persist. Illegal snares set for bushmeat can maim gorillas. Habitat encroachment continues near park boundaries, particularly in Kisoro and Kabale districts.

Disease transmission, especially respiratory infections introduced by humans, remains a serious concern due to genetic proximity.

The Eastern Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri) is listed as Critically Endangered. Fewer than 6,800 individuals remain across fragmented ranges in eastern DRC. Prolonged conflict, weak law enforcement, and mining activity in and around protected areas like Kahuzi-Biega National Park have severely undermined conservation efforts.

Grauer’s gorillas are monitored by several regional groups, including FZS and the Wildlife Conservation Society. Community sensitisation programs have shown modest success, especially near Walikale and Bukavu. However, militia presence in remote zones still prevents consistent fieldwork and anti-poaching patrols.

The Western Lowland Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla), though more numerous, also faces significant pressure. It is classified as Critically Endangered, with population estimates ranging from 100,000 to 250,000. However, these figures remain provisional due to dense forest cover and limited access to remote territories.

Ebola outbreaks in Congo and Gabon have decimated entire populations. Poaching for meat and live infants continues in some regions despite international protection. Logging roads open up otherwise inaccessible areas, increasing human contact and risk of exploitation.

Several sanctuaries and field sites offer hopeful models. Odzala Discovery Camps and Dzanga-Sangha Protected Area both integrate tourism with monitoring and habitat protection. Moreover, NGOs like Gorilla Organisation and WCS support long-term research and ranger employment in remote districts.

Appreciating Diversity Among Gorillas

Recognising the distinctions within the gorilla genus refines how we speak, plan, and act across conservation, tourism, and science. The subject demands that level of accuracy.

Few species receive such targeted global attention. Even fewer carry responsibilities divided across borders, funding systems, and public expectations. Gorillas are one of them.

That clarity on who they are and where they live matters. If your work touches this subject in any way, then precision is part of your role too.