The Great Migration refers to the year-round, large-scale movement of over 1.5 million wildebeest, alongside hundreds of thousands of zebra and Thomson’s gazelle, across the Serengeti-Masai Mara ecosystem.

This cyclical phenomenon spans the international boundary between northern Tanzania and southwestern Kenya. It follows a clockwise loop covering approximately 3,000 kilometres in response to rainfall and grass availability.

Most of the migration activity takes place in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park. However, between July and October, significant herds enter Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve. These movements include the dramatic river crossings at the Mara and Grumeti rivers, which often attract predator activity.

Wildebeest calving begins around late January to early March, primarily in the Ndutu region of the southern Serengeti. The migration continues through various ecological zones, each presenting different photographic and ecological highlights.

If you’re seeking clarity on when, where, and how to witness this event, this guide provides structured insight to help you align your visit with the natural timing of the migration.

What Is the Great Migration?

The Great Migration refers to the uninterrupted, circular movement of large herbivores across the Serengeti-Masai Mara ecosystem.

It involves over 1.5 million wildebeest, approximately 250,000 zebra, and nearly 400,000 Thomson’s gazelle. These species move in search of water and fresh grass, tracking rainfall patterns across an estimated 30,000 square kilometres of protected land.

Their movement forms a closed loop, dictated not by destination but by seasonal shifts in grazing quality.

The loop begins and ends in the southern Serengeti, forming a self-sustaining ecological circuit that unfolds throughout the year. This constant motion supports breeding, feeding, and survival cycles, not just for grazers, but also for predators that depend on them.

The key species involved include:

- Wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus): Over 1.5 million individuals form the core of the migration. Their synchronised calving and sensitivity to rainfall make them the primary drivers of movement.

- Zebra (Equus quagga): Approximately 250,000 zebras accompany the wildebeest, often leading the herds. They feed on taller grasses, which clears space for wildebeest to access shorter, more nutritious growth.

- Thomson’s gazelle (Eudorcas thomsonii): Nearly 400,000 follow behind. Their digestive systems favour what remains after wildebeest and zebra pass through.

- Eland, Grant’s gazelle, and others: Present in smaller numbers and follow loosely aligned movement patterns.

This migration responds directly to ecological signals.

Rainfall patterns across the plains trigger the growth of short grasses, especially Chloris and Themeda species, which wildebeest favour.

Calving aligns with the rainy season between late January and March, when high-nutrient grasses support milk production and juvenile survival.

Geographically, the migration spans from the southern Serengeti in Tanzania to the northern reaches of Kenya’s Masai Mara.

These zones include areas such as Ndutu, Seronera, Grumeti, the Mara Triangle, and Loita Hills. The loop does not follow a straight line; rather, it forms a clockwise, often fragmented circuit that adjusts annually based on microclimate variability.

Some assume the Great Migration is a dramatic, single-time event, usually involving river crossings.

In reality, it is a continuous ecological mechanism. Its visibility depends entirely on timing and rainfall. If you’re planning to observe it, understanding this continuity is essential.

READ ALSO: Hiking Safaris in Uganda

The Migration Route – Month-by-Month

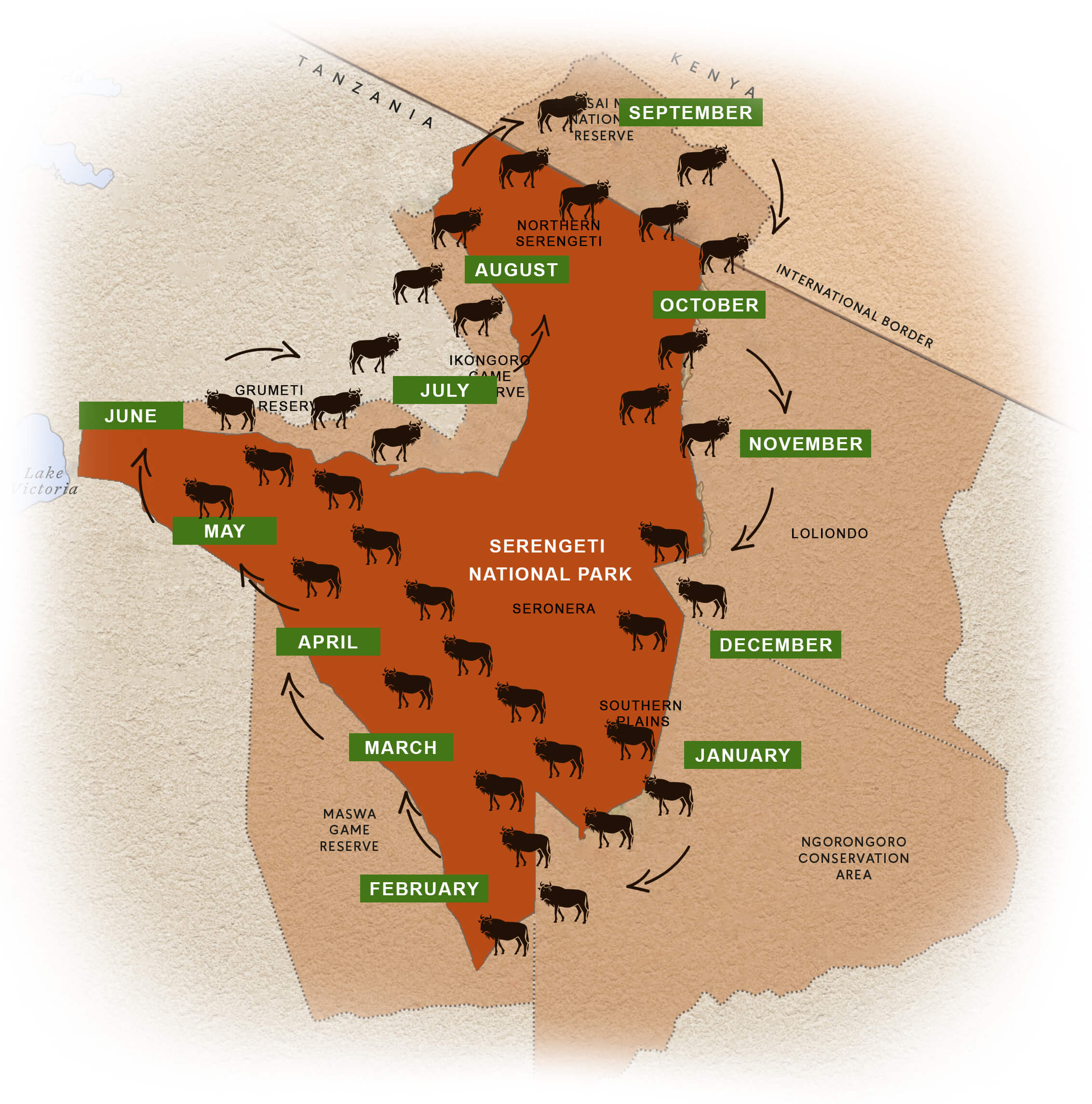

The Great Migration follows a roughly clockwise movement pattern across the Serengeti-Masai Mara ecosystem, spanning southern, central, and northern Serengeti in Tanzania and extending into Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve.

The movement is not fixed to dates but closely tied to regional rainfall patterns, vegetation regrowth, and the reproductive cycles of wildebeest. Though slight variations occur annually, the following month-by-month guide reflects the most consistently observed pattern used by professional guides, researchers, and operators across East Africa.

January to March – Southern Serengeti and Ndutu Calving Grounds

From January through early March, the herds concentrate in the southern Serengeti, particularly around the Ndutu and Lake Masek areas, situated in the Ngorongoro Conservation Area.

The short rains of November and December transform these plains into temporary grasslands dominated by nutrient-rich shoots of Themeda and Chloris species.

This high-protein forage triggers the onset of calving.

Calving peaks in early February, when over 500,000 wildebeest give birth within a span of roughly two to three weeks.

The open plains provide wide visibility, offering some protection against predators, though lions (Panthera leo), spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) remain highly active.

Predation rates increase significantly during this period, especially as newborn calves struggle to stand and keep pace.

Zebra and gazelle occupy similar areas but follow slightly staggered reproductive timelines.

By late March, rainfall begins to decline, prompting the herds to shift gradually northwest in search of denser, more resilient grass cover.

April to May – Transition Through Central Serengeti

In April and May, the herds begin a slow but deliberate movement northward, crossing into central Serengeti zones such as Seronera, Moru Kopjes, and the western plains near Simiyu.

The long rains, which begin around mid-March, continue into May, replenishing water sources and encouraging grass regeneration in transitional zones.

Wildebeest advance in scattered columns rather than in one cohesive front. The terrain here includes river valleys, granite outcrops, and slightly denser grassland, which allows the herds to rest, feed, and regroup.

Predators are less concentrated than during calving but remain active in wooded areas and watercourses.

Due to wet and sometimes inaccessible roads, few tourists visit this area in April.

However, professional operators consider this period ideal for observing herd dynamics without peak-season congestion.

The migration remains within Tanzanian boundaries, spreading out over hundreds of kilometres.

June – Western Corridor and Grumeti River

By June, as the rains taper off, the herds gather in the western Serengeti, particularly the Kirawira and Grumeti Reserve zones.

This area features thicker woodland and the first major river obstacle: the Grumeti River. Though less dramatic than the Mara River crossings later in the year, the Grumeti presents its challenges, especially due to high water levels and the presence of Nile crocodiles (Crocodylus niloticus), some over five meters in length.

The crossings are unpredictable. Not all herds cross simultaneously, and some linger in the surrounding areas for weeks.

Rutting behaviour becomes more visible during this phase. Male wildebeest engage in territorial displays and vocalisations, marking the peak of breeding activity.

By the end of June, the leading herds begin to turn northeast, following drying winds and thinning grasses toward the Lobo and Bologonja areas.

July to August – Northern Serengeti and Mara River Crossings

July marks the onset of the most anticipated period of the migration: the Mara River crossings.

By mid-July, herds cluster in the northern Serengeti, especially around Kogatende, Lamai Wedge, and the southern banks of the Mara River.

These areas are defined by undulating grassland, dense thickets, and steep riverbanks that often complicate crossings.

River crossings do not follow a fixed schedule. Herds may arrive, retreat, and regroup multiple times before attempting.

During high river flow, mass drownings and predation increase. Crocodiles concentrate near preferred crossing points, while lion prides and hyenas patrol the surrounding slopes.

By August, many herds have successfully crossed into Kenya’s Masai Mara National Reserve. However, significant numbers remain in the northern Serengeti. The Mara Triangle and Musiara Gate areas in Kenya see heavy wildebeest concentrations, while zebras continue northward into the Loita Hills.

September to October – Masai Mara and Northern Tanzania Fringe

Through September and into October, the herds spread across the Masai Mara ecosystem.

Pastures remain plentiful due to Kenya’s cooler highland climate and recent rain activity.

Predator activity remains elevated, with known lion prides such as the Marsh, Paradise, and Ridge groups frequently observed in pursuit of young or isolated wildebeest.

However, by mid-October, signs of retreat become visible.

Grass cover diminishes as dry winds return. The leading groups begin to cross southward again, moving back across the border into northern Serengeti.

Some remain in Kenya longer, depending on local rainfall, but the majority prepare for the southbound loop.

Professional planners regard September as an optimal time for safaris, particularly for observing well-distributed herds and predator dynamics.

Access to crossing points becomes easier, although visitor numbers also peak during this window.

November to December – Return to Southern Serengeti

As the short rains return around early November, the herds commence their final leg southward.

Movement accelerates through Lobo, Bologonja, and back toward Seronera. By late December, significant numbers have reached Ndutu, once again populating the calving grounds.

This phase includes fragmented movements, with different groups arriving at different times depending on rainfall variation across the region.

The ecosystem recycles itself: grazing pressure renews the soil, predators track the herds, and park authorities prepare for the next cycle of monitoring and management.

If you’re aiming to observe this phase, planning flexibility is essential. Some years see early returns, while others remain disjointed until mid-December.

Best Time to See the Great Migration

No single month defines the best time to see the Great Migration.

The experience changes depending on which phase of the migration is active, where the herds are concentrated, and what you intend to observe.

Some visitors prioritise dramatic river crossings, while others seek quieter conditions or focus on ecological dynamics such as calving or predator behaviour.

Understanding these distinctions allows for informed scheduling depending on what you want to see. Broken down below are the best times for what, explained in detail.

1. Calving and Juvenile Observation (February)

If your goal is to observe the mass birth of wildebeest calves and associated predator-prey dynamics, the second half of January through early March offers the highest ecological value.

During this period, over 500,000 wildebeest give birth within a relatively compact area, primarily in the Ndutu sector of the southern Serengeti. These short-grass plains offer clear visibility, making it easier to observe newborns, hunting behaviours, and maternal herd structure.

2. Mara River Crossings and Herd Density (July to September)

Between July and September, the migration reaches the northern Serengeti and crosses into Kenya’s Masai Mara.

This is the most commercially promoted phase of the migration, largely due to the dramatic river crossings along the Mara River.

These crossings are unpredictable and sometimes delayed by changes in rainfall, but when they occur, they produce high-density visuals of mass movement, crocodile predation, and panic-driven stampedes.

However, you need to know that this window also attracts the largest number of visitors, and congestion near known crossing points is common.

3. Low-Traffic Viewing and Scattered Herds (April to May, November)

For visitors seeking a less commercial experience and more dispersed wildlife movement, April, May, and November offer distinct value.

These periods align with the long rains (April–May) and short rains (November), during which herds travel through transitional zones: the central Serengeti in the former, and northern Serengeti into southern Serengeti in the latter.

These phases lack tightly packed herds or river crossings. Instead, animals move in extended lines and breakaway groups, often interacting with semi-resident herds and territorial predators.

Although photography conditions vary due to cloud cover and occasional rain, the absence of peak visitor volume allows for uninterrupted observation and broader ecological context.

These months present an opportunity for informed observers who prefer behaviour over density, movement over spectacle.

READ ALSO: Essential Safari Photography Tips for Tourists

4. Predator Activity and Behavioural Events (January–March, August–September)

Visitors interested in predator behaviour and ecological interactions should focus on January through March, during the calving phase, and August through September, when river crossings trigger dispersal and regrouping.

Both windows present high rates of predation, stalking, and territorial conflict, especially from lions, hyenas, and crocodiles.

In the southern Serengeti, calving brings predators within close range of herds, often in open plains. In the north, the chaos of river crossings fragments the migration, isolating weak or panicked individuals.

For those studying food chains, stress behaviour, or maternal defence strategies, these two windows offer a structured lens into the ecological pressure points of the migration system.

Conclusion: What makes the Great Migration Unique

The Great Migration functions as a self-regulating ecological mechanism that sustains East Africa’s grassland ecosystems.

Wildebeest act as mobile grazers, shaping vegetation cycles, dispersing seeds, and redistributing nutrients across thousands of square kilometres.

Their synchronised movement supports soil health and creates predictable prey availability, which stabilises predator populations across the Serengeti-Masai Mara system.

This ecological precision elevates the migration from a wildlife spectacle to a central component of regional ecosystem function.

What makes the migration particularly rare is its acute responsiveness to short-term rainfall and vegetation growth.

Rather than following static routes, herds adapt dynamically to rainfall patterns, often adjusting their movement in response to hyper-local conditions. This reactive behaviour makes the system difficult to model and nearly impossible to replicate.

As one of the last remaining intact large-mammal migration systems on the planet, it continues to inform ecological research and global conservation strategies.