The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) identifies and protects locations of global cultural or environmental importance. These are known as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, located all over the world, including Uganda

Each site must meet strict criteria. These include cultural significance, ecological uniqueness, and the ability to communicate universal value across generations.

UNESCO status signals global recognition. It adds layers of responsibility to conserve and manage each site with both scientific and community-driven frameworks.

It also attracts international collaboration, conservation funding, and educational initiatives. These help improve management practices and research opportunities across sectors.

In Uganda, UNESCO heritage sites sit at the intersection of cultural continuity, ecological integrity, and sustainable tourism. They reflect identity and support long-term planning goals.

Each listed site contributes to the broader mission of responsible visitation. They promote education, community engagement, and policy coordination across local and national platforms.

UNESCO designation helps align conservation goals with contemporary development strategies.

When managed well, these sites offer experiential travel options that support local economies while maintaining ecological and cultural authenticity.

Their inclusion in global conservation frameworks also positions Uganda as a steward of places that matter to humanity.

Bwindi Impenetrable National Park

Bwindi earned UNESCO World Heritage status in 1994, following a rigorous evaluation of its ecological value and conservation framework. It met natural criteria (ix and x).

Criterion (ix) focused on ongoing ecological and biological processes. Criterion (x) recognised the site’s importance for in situ conservation of endangered species, especially the mountain gorilla.

The nomination came at a pivotal time. Uganda had just begun stabilising after years of political unrest. Conservation institutions were rebuilding. Community engagement was gaining traction.

UNESCO’s recognition helped strengthen protection measures and attract international partnerships. It aligned conservation goals with Uganda’s broader agenda of biodiversity management and eco-tourism.

The inscription also sent a message. Bwindi mattered—not just to Uganda, but to global conservation science.

Ecological and Biological Significance

Bwindi forms part of the Albertine Rift montane forest system. Its location on the edge of the western arm of the East African Rift provides high ecological diversity.

The park supports 120 mammal species, over 350 bird species, and 10 primate species. Among them, the critically endangered mountain gorilla remains the most closely monitored.

Botanical surveys have identified at least 160 tree species and over 100 fern species. Many are endemic or near-endemic to the region.

Its compact forest structure contains steep valleys, ridges, and rivers. These physical features create multiple microhabitats that support ecological variation and species specialisation.

Community Involvement and Conservation Strategy

When Uganda restructured its conservation model in the early 1990s, it placed communities at the centre of protected area governance. Bwindi became a pilot site.

Today, the Uganda Wildlife Authority implements community tourism zones, revenue-sharing agreements, and negotiated forest access rights.

Local associations engage in eco-guiding, handicraft production, and agricultural cooperatives. Their participation builds economic alternatives and lowers dependency on forest resources.

The Bwindi Trust Fund and several NGOS continue to support community-based monitoring, conflict resolution training, and conservation education.

This collaborative approach helped stabilise the gorilla population. It also strengthened relationships between protected area staff and neighbouring households.

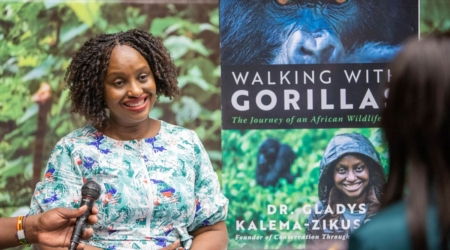

Gorilla Tracking and Visitor Management

Gorilla tracking permits regulate visitation and fund site operations. Each permit corresponds to one hour with a specific gorilla family, under strict behavioural guidelines.

Permits are limited to avoid stress on the animals. Visitor briefings emphasise movement control, vocal restraint, and a minimum distance.

Trained guides lead each tracking group. They provide ecological interpretation and ensure group compliance with wildlife safety codes.

During peak periods, overnight capacity in the park’s periphery reaches its limit. Planners continue to review carrying capacity thresholds and infrastructure resilience.

Bwindi’s tourism strategy focuses on controlled access, interpretation quality, and ecological responsibility. This model keeps the experience meaningful while protecting the core conservation mission.

Rwenzori Mountains National Park

Rwenzori Mountains National Park entered the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1994 under natural criteria (vii) and (x). The nomination emphasised scenic and ecological relevance.

Criterion (vii) considered the park’s visual impact, especially its snow-capped peaks and glacial valleys. Criterion (x) addressed its role in conserving species unique to the Albertine Rift.

By the early 1990s, government institutions had begun formalising protected area policies. The Rwenzori region, previously impacted by low-level conflict and informal extraction, required urgent conservation status.

UNESCO recognition strengthened that shift. It supported a restructured management plan, new visitor regulations, and ecological research partnerships. The listing created long-term incentives for protection.

The process highlighted a key point. Conservation and tourism in the Rwenzori had to work together, or both would struggle.

Cultural Significance and Oral Traditions

The Rwenzori range holds deep meaning for the Bakonzo and other communities living along its foothills. Many consider the peaks sacred.

Traditional oral narratives describe the mountains as the home of ancestral spirits and rainmakers. Ritual practices still occur near river mouths and highland sites.

UNESCO acknowledged this intangible cultural layer during its evaluation. The mix of ecological importance and cultural reverence created a rare dual-value conservation zone.

Park authorities maintain cultural access routes that permit specific rites under approved supervision. These collaborations protect local belief systems while reinforcing respect for protected area boundaries.

Biological Importance and Altitudinal Zoning

Rwenzori’s ecological character changes rapidly with altitude. The park supports five distinct vegetation zones, each hosting a specialised ecological community.

Lower zones contain montane forest, bamboo, and mixed hardwood species. Mid-elevation areas feature giant heathers and afro-alpine scrub. Above 4,000 meters, icefields and rock dominate.

This vertical stratification supports high endemism. Rare bird species, amphibians, and flowering plants thrive in isolated pockets with limited human interference.

The park also serves as a catchment for the Nile basin. Glacial meltwater contributes to year-round river flow that sustains lowland agriculture and fisheries.

Trekking Circuits and Site Management

Rwenzori offers some of Uganda’s most technically demanding trekking circuits. Climbers require permits, porters, and registered guides due to shifting weather and elevation gain.

Popular routes include the Central Circuit and Kilembe Trail. These routes pass through ranger stations, overnight camps, and alpine huts with fixed-use guidelines.

The Uganda Wildlife Authority uses these circuits to enforce visitor limits, trail maintenance schedules, and mountain safety protocols.

Interpretation teams provide geological and ecological insights during hikes. Their presence improves visitor awareness while reinforcing park management policies.

Permit systems fund search and rescue units, erosion control, and biological monitoring. These tools form the operational backbone of Rwenzori’s sustainable tourism framework.

Tombs of Buganda Kings at Kasubi

Kasubi was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001 under cultural criteria (i), (iii), (iv), and (vi). These recognised its architectural form, historical continuity, and living cultural practices.

The site contains the royal tombs of four kings of the Buganda Kingdom. It sits on land once occupied by the Kabaka’s palace, originally built in 1882.

The transition from palace to burial site followed Buganda royal tradition. Each Kabaka who dies is buried in a royal tomb, along with sacred objects and regalia.

Kasubi remains central to the identity of the Ganda people. It functions as a spiritual site, ritual space, and political symbol tied to the monarchy.

The nomination process focused on preserving both built structures and intangible customs. UNESCO supported this approach by framing Kasubi as a living cultural site rather than a static monument.

Architectural Form and Material Culture

The main structure, known as Muzibu Azaala Mpanga, follows traditional Ganda construction principles. Its large circular dome is supported by wooden poles and woven reeds.

Builders used organic materials, including grass thatch, fig tree bark cloth, and wooden pegs. These materials require routine maintenance through established community rituals.

Kasubi exemplifies built heritage grounded in local cosmology and material knowledge. The site’s architectural design connects functional spaces to symbolic hierarchies.

Supporting structures include houses for ritual guards, areas for royal widows, and compounds used during cultural ceremonies. Each serves a defined role within the ceremonial layout.

Damage and Restoration Initiatives

In 2010, a fire destroyed the central tomb structure. The cause remains unresolved, though investigations followed both traditional and institutional channels.

After the fire, UNESCO placed Kasubi on the List of World Heritage in Danger. This activated emergency funding and mobilised conservation professionals.

Reconstruction followed traditional guidelines overseen by cultural leaders and technical experts. Craftsmen retrained in bark cloth making, thatching, and carpentry contributed to the process.

The government and the Buganda Kingdom developed a joint management framework. This included security measures, documentation protocols, and cultural access policies.

UNESCO monitors the site’s recovery through periodic reports and technical missions. Their involvement ensures that both conservation standards and cultural values remain balanced.

Cultural Function and Urban Challenges

Kasubi sits within the rapidly expanding Kampala metropolitan zone. Construction pressure and land use changes continue to surround its perimeter.

Despite this, the site maintains its ceremonial function. It hosts rituals, initiation practices, and traditional court proceedings tied to the Buganda monarchy.

Cultural custodians, known as the Nalinya and Katikkiro, oversee site access, ceremonial schedules, and daily rituals. Their presence keeps the site’s function active and relevant.

Urban development has increased footfall and noise levels around the perimeter. The management team works with city planners to define buffer zones and reduce external impacts.

Kasubi remains a cultural anchor. It links Buganda’s past, present, and future through ritual, architecture, and ancestral continuity.

Impact on Tourism

UNESCO status for the above heritage sites shapes the tourism experience in Uganda by increasing global visibility and institutional confidence. It brings structured investment, visitor regulation, and long-term planning into protected sites.

Tour operators use the designation as a quality signal. It assures visitors that these sites follow international standards for conservation, access, and interpretation.

In Bwindi, the permit-based gorilla tracking system controls visitor flow. It prevents overuse while creating predictable revenue streams that support park operations and local partnerships.

Gorilla tracking generates significant income. Permit fees fund ranger salaries, community development projects, and veterinary services for the monitored gorilla groups.

Accommodation infrastructure around Bwindi has grown steadily. Lodges, homestays, and eco-camps offer guided nature walks, cultural experiences, and multi-day wildlife packages with clear impact guidelines.

Rwenzori attracts trekkers seeking high-elevation adventure under regulated conditions. Licensed porters, certified guides, and logistical support ensure both safety and environmental control.

The park’s entry fees support rescue services, ecological monitoring, and trail maintenance. These systems allow long-distance hiking to function without compromising conservation objectives.

Kasubi operates in a different tourism niche. It supports cultural programming, heritage interpretation, and education-based visits coordinated with the Buganda Kingdom and local guides.

The tombs attract school groups, faith-based delegations, and cultural researchers. Each visit contributes to awareness and site sustainability through small access fees and structured tours.

Across all three heritage sites in Uganda, UNESCO status helps standardize expectations. It links marketing, policy, and training under shared frameworks that prioritise long-term site protection.

Future Opportunities

Expanding the UNESCO Portfolio

Uganda holds untapped potential in its Tentative UNESCO Heritage Sites List. Sites like Nyero Rock Paintings and Bigo bya Mugenyi show high cultural and archaeological value.

Government agencies and academic institutions have begun updating nomination dossiers. These submissions must meet UNESCO’s technical and community-based criteria to move forward.

Each potential site brings local benefits. They create new visitor circuits, support regional identity, and strengthen heritage education among younger populations.

A coordinated national nomination strategy could help fast-track these listings while linking them to domestic tourism priorities.

Strengthening Sustainable Tourism Models

Site managers can scale up sustainability by improving data collection, trail zoning, and waste management systems. These upgrades help align visitation with conservation thresholds.

In Bwindi and Rwenzori, planners continue to test eco-certification programs for lodges and guides. These programs measure emissions, water use, and supply chains.

Kasubi’s future depends on balancing access and ritual protocol. Scheduled tours, cultural briefings, and visitor orientation centers can help mediate that balance.

Tourism boards may also introduce multi-site passes that link all three UNESCO sites. This approach increases cross-site learning and extends average visitor stay.