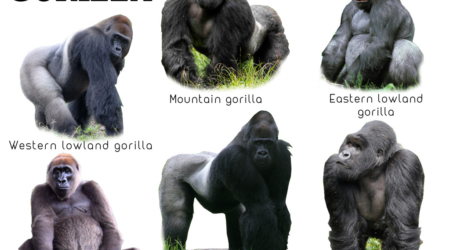

Mountain gorillas are a subspecies of the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei). They live in two isolated populations across East Africa.

One group lives in the Virunga Mountains — a volcanic range spanning parts of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The second group lives in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable National Park.

Mountain gorillas prefer montane and bamboo forests at altitudes between 2,200 and 4,300 meters. These ecosystems are cool, humid, and biologically complex.

They live in stable social groups of 10 to 30 individuals. Each group centres around a dominant silverback, who controls movement and protects the members.

These apes share over 98% of human DNA. They show high cognitive ability, use vocal communication, and maintain strong social bonds through grooming, play, and body language.

Physically, they’re powerful animals. Adult males can weigh up to 200 kilograms. Their thick fur helps them tolerate cold temperatures that would affect other primates.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists mountain gorillas as endangered. Their limited distribution and small population size make them highly sensitive to environmental and human threats.

Why are mountain gorillas endangered?

Mountain gorillas face a set of overlapping pressures. Each one alone is serious. Together, they create a continuous strain on a species already operating on thin margins.

1. Habitat loss

Habitat loss is the primary threat to mountain gorillas. It develops gradually, but the damage is often long-term and difficult to reverse.

Population growth near protected areas increases demand for land. Forests are cleared for farming, fuel, and settlement, reducing the space mountain gorillas need to survive.

In Uganda and parts of the DRC, farmland now borders protected forests. This direct contact creates tension, competition, and risk for both people and gorillas.

When the forests become fragmented, gorilla groups lose their ability to move between regions. That isolation increases the chance of inbreeding and weakens the population over time.

Even selective logging disrupts key food sources and nesting areas. These small changes reduce the quality of the habitat and limit feeding options.

Without strong land-use planning or enforcement, forest loss continues. Once cleared, a few of these areas recover in time to be ecologically useful again.

2. Poaching and illegal trade

Poaching has long threatened mountain gorillas, though its form has shifted over time. Today, most gorillas are harmed indirectly, rather than hunted deliberately.

Wire snares, set for bushmeat species like antelopes or duiker, often catch gorillas instead. These traps injure or kill individuals, especially infants and juveniles.

Direct poaching still occurs, though rarely. Some individuals are targeted for body parts, status symbols, or illegal display. Infant gorillas may be taken for private collections.

Gorilla groups rely on cohesion. When a silverback is killed, the group may split or scatter, increasing the risk of infant mortality and exposure to other threats.

Weak law enforcement and porous borders make it difficult to stop illegal activity. In areas of political instability, monitoring is limited and reporting gaps persist.

Even a small number of poaching incidents can cause serious harm. Mountain gorillas reproduce slowly, so each loss sets back population recovery.

3. Disease

Disease poses a serious threat to mountain gorillas due to their close genetic similarity to humans. Many common human viruses can infect them easily.

Respiratory illnesses are the most frequent concern. Even mild infections, like the common cold or influenza, can spread rapidly and become fatal to gorillas.

Mountain gorillas live in groups with close physical contact. This social behaviour allows pathogens to move quickly through a group once introduced.

Tourism, research, and monitoring bring people into close range. While valuable for conservation, this interaction increases the likelihood of disease transmission from humans to gorillas.

Park authorities enforce strict distancing rules and health checks. However, enforcement varies depending on local resources, weather conditions, and visitor compliance.

Veterinary teams monitor health and treat injuries or illnesses when possible. Still, prevention remains more effective than intervention in most situations.

Because gorillas have low genetic diversity and slow reproductive rates, disease outbreaks can have long-term effects on population recovery.

4. Conflict and political instability

Armed conflict in parts of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo has repeatedly disrupted conservation work in mountain gorilla habitats.

During periods of conflict, park staff often evacuate or suspend patrols. This leaves wildlife more vulnerable to poaching, encroachment, and illegal logging.

Militia groups sometimes operate within or near protected forests. Some use parkland as cover, setting up camps or controlling access to remote areas.

In conflict zones, conservation infrastructure deteriorates. Communication breaks down, ranger stations are abandoned, and long-term projects stall or collapse entirely.

Local communities living near these areas also suffer. When livelihoods become unstable, pressure on nearby forests increases. People rely more heavily on natural resources to survive.

Funding often shifts away from conservation during crises. Donors reallocate support to humanitarian aid, and governments focus on security rather than environmental protection.

Even after conflict ends, recovery is slow. Rebuilding trust, infrastructure, and monitoring systems takes time, often years.

5. Climate Change

Climate change is not the most immediate threat to mountain gorillas, but it does influence the long-term stability of their environment.

Shifting rainfall patterns and temperature changes can alter vegetation cycles. This affects the availability and seasonality of key food plants in gorilla habitats.

Prolonged droughts may reduce water sources and plant growth. This leads to nutritional stress, especially for groups with limited range or few fallback feeding options.

Increased storm intensity can also damage forest structure. Treefall and erosion disrupt nesting areas and reduce forest cover, particularly at higher elevations.

These environmental shifts add pressure to already small populations. When combined with habitat loss and fragmentation, the effect becomes more difficult to manage.

Climate change also affects human activity. Poor harvests and unpredictable weather increase local dependence on forest resources for food and fuel.

The impact is gradual but cumulative. Monitoring long-term climate patterns is now part of many protected area management plans.

Read Also: Impact of Climate Change on Mountain Gorillas.

Conservation Efforts that are Working

Despite ongoing pressure, targeted conservation has stabilised mountain gorilla numbers over the past two decades. This success results from long-term strategies, consistent funding, and collaboration across sectors.

We’ll break down key actions into five focus areas: patrol and law enforcement, community engagement, habitat protection, veterinary support, and international partnerships.

a) Anti-Poaching Patrols and Law Enforcement

Daily patrols by trained rangers have reduced poaching significantly in core gorilla zones. These teams track illegal activity, remove snares, and deter intrusion.

Most rangers come from local communities. Their knowledge of the area, combined with regular training, improves response time and data collection.

In some parks, patrols use GPS tracking and mobile reporting. This improves accountability and allows faster coordination when threats are detected.

Legal frameworks also matter. National laws now carry stronger penalties for poaching, wildlife trade, and unauthorised entry into protected areas.

However, enforcement still depends on resources and political will. Areas with consistent ranger presence see better outcomes than those with irregular coverage.

b) Community-based conservation

Mountain gorilla conservation depends on the cooperation of people living near protected areas. Without their involvement, long-term protection is not possible.

Many conservation programs now include revenue sharing from tourism. A portion of park income funds infrastructure, health care, and education in nearby communities.

This approach builds local support. When communities see direct benefits, they become less likely to engage in activities that harm protected areas.

Employment also plays a role. Parks often hire residents as rangers, guides, porters, and monitors. These jobs provide stable income and reduce pressure on natural resources.

Education programs in schools and villages promote conservation awareness. They help build long-term understanding of why protection matters beyond short-term gain.

In some areas, local cooperatives receive grants to develop small businesses. These alternatives reduce reliance on forest products and create economic incentives for conservation.

c) Habitat protection and reforestation

Securing the mountain gorilla habitat remains a central goal in conservation planning. Most gorillas live within formally designated protected areas managed by national park authorities.

These areas include Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda, Bwindi and Mgahinga in Uganda, and Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Buffer zones around these parks help reduce edge pressure. They allow limited community use while preventing deeper encroachment into core gorilla habitat.

Reforestation projects target degraded land near existing parks. Native tree species are planted to restore ecological function and expand habitat for gorilla groups.

Some programs also reconnect forest patches. These corridors allow gorilla groups to move safely between areas, improving genetic diversity and group stability.

Mapping tools now support habitat planning. Satellite imagery and field data help identify high-risk zones and track deforestation in real time.

Land security is equally important. Park boundaries must be legally recognised and respected by both the government and local stakeholders.

d) Health monitoring and veterinary care

Mountain gorilla conservation includes proactive veterinary care. Specialised teams monitor health, treat injuries, and respond to disease outbreaks in the field.

The Gorilla Doctors program provides clinical care directly in the forest. Their teams operate in Rwanda, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Routine health checks involve visual assessments, faecal sampling, and behaviour monitoring. These checks help detect early signs of infection or distress within gorilla groups.

When necessary, veterinary teams conduct field interventions. These may involve removing snares, administering antibiotics, or providing wound care under controlled sedation.

Preventive measures are equally important. Strict guidelines govern human access to gorillas, including health screenings, distance rules, and limits on group size.

Research links human respiratory infections to gorilla deaths. This connection makes health protocols a critical part of daily park operations and visitor management.

Health data also supports broader conservation planning. Understanding disease trends helps teams prepare for future risks and improve response strategies.

What you can do

Mountain gorilla conservation requires public support beyond protected areas. Individuals can contribute meaningfully through informed choices, financial support, and advocacy.

Support established conservation organisations. Look for transparency, long-term programs, and proven partnerships with local authorities and communities.

Donate directly to field-based programs. Contributions often fund ranger salaries, veterinary care, training, and essential supplies used in daily operations.

Avoid products linked to illegal wildlife trade or unsustainable land use. Responsible consumption reduces pressure on critical habitats across the region.

If visiting parks that protect gorillas, follow all health and distance protocols strictly. These rules exist to prevent disease and minimise stress on the animals.

Use your platform to raise awareness. Share factual information and support policies that prioritise ecological protection, sustainable tourism, and long-term funding.

Stay informed. Conservation outcomes improve when the public demands accountability from both governments and donor institutions.